I have spent the better part of two decades on factory floors, watching industrial drying and processing technologies evolve. For years, we relied on rotary kilns and gas-fired furnaces. They were reliable, sure, but they were also massive energy hogs. You could practically see the dollars floating up the smokestack.

In recent years, the conversation has shifted. Plant managers are no longer just asking about capacity; they are asking about efficiency and carbon footprints. This is where microwave pyrolysis enters the picture. It is not just an alternative; in many specific applications, it is a complete replacement for the old ways of thermal decomposition.

Whether you are dealing with waste tire recycling, biomass conversion, or hazardous waste treatment, the technology you choose dictates your margins. Brands like Nasan have been instrumental in making this technology accessible, moving it from lab-scale experiments to robust industrial machinery. But is it right for your specific production line? Let’s look at the numbers and the engineering reality.

Understanding the Mechanics of Microwave Pyrolysis

To make an informed decision, you have to understand the fundamental difference in heat transfer. Traditional pyrolysis relies on external heating. You burn gas or oil to heat a reactor wall, and that heat slowly conducts into the material. It is a slow, uneven process.

Microwave pyrolysis works differently. It utilizes dielectric heating. The energy penetrates the material directly, causing the molecules to vibrate and generate heat from within.

This "inside-out" heating mechanism eliminates the thermal lag you get with conventional ovens. I have seen processing times cut by 50% or more simply because we didn't have to wait for the heat to travel from the surface to the core of the feedstock.

The Economic Case: CAPEX vs. OPEX

When you look at the price tag of a high-end microwave system, you might hesitate. The initial Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) is often higher than a standard rotary kiln. However, in the industrial drying and processing game, the sticker price is the wrong metric. You need to look at Operational Expenditure (OPEX).

Microwave systems are electrically driven. They can be turned on and off instantly. There is no long warm-up phase where you are burning fuel just to get the chamber up to temperature.

Furthermore, because the heating is selective, you aren't wasting energy heating the air or the steel structure of the kiln—only the material itself absorbs the energy. Over a five-year period, the energy savings often eclipse the initial cost difference.

Material Suitability and Yield Quality

One of the most frequent questions I get regarding microwave pyrolysis is about the quality of the output. In traditional high-temperature methods, you often get a "crust" on the material, or uneven charring.

With microwaves, the temperature distribution is significantly more uniform. This is crucial for high-value applications. For instance, if you are recovering carbon black from tires, the structural integrity of that carbon black matters.

I have worked with setups where the yield of bio-oil and gas was significantly higher with microwave assistance because secondary cracking (which destroys valuable chemicals) was minimized.

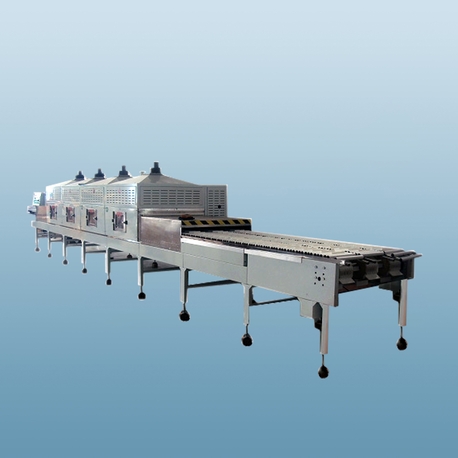

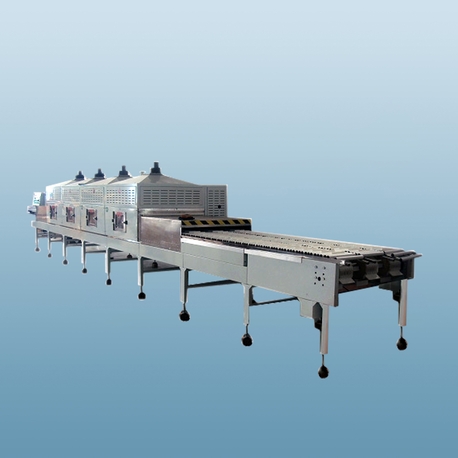

Industrial Design and Throughput

This is where the rubber meets the road. A lab machine is one thing; a machine that runs 24/7 is another. Modern industrial designs use continuous conveyor belts or screw augers.

Companies like Nasan have refined the continuous feed system. This is critical. You cannot afford a batch process in a high-volume plant. You need raw material going in one end and finished product coming out the other, non-stop.

The modularity of these systems is also a benefit. If you need more capacity, you don't necessarily need to build a new building; you often just add more magnetron modules to the line.

Energy Efficiency and Carbon Credits

We cannot ignore the regulatory environment. Carbon taxes and emission limits are tightening globally. Gas-fired pyrolysis releases significant NOX and SOX emissions directly from the combustion needed to heat the reactor.

Microwave pyrolysis is electrically powered. If your grid source is green (or if you have on-site solar), your process can be effectively carbon-neutral.

I have seen companies use this as a marketing tool. Selling "green" carbon black or biochar produced with zero direct emissions allows them to charge a premium. It turns a compliance headache into a sales feature.

The Role of Moisture Content

A nuanced point that often trips up operators is moisture. In traditional drying, water is the enemy that consumes massive amounts of fuel. In microwave systems, water is actually a facilitator.

Water is an excellent absorber of microwave energy. A small amount of moisture can help kickstart the heating process, acting as a susceptor to raise the temperature quickly before the pyrolysis reactions take over.

However, you still need to balance this. Too much water means you are just boiling steam. Finding that sweet spot in feedstock preparation is where the expertise comes in.

Maintenance and Durability Factors

Let’s be honest about the downsides. Microwave magnetrons are consumables. They have a lifespan (usually a few thousand hours) and they need replacing.

In the early days, replacing a magnetron meant shutting down the whole line. Modern designs are smarter. They use redundancy. If one magnetron fails, the others compensate, and you can swap the faulty unit during scheduled maintenance.

The absence of moving parts inside the heating zone (unlike the heavy tumbling of a rotary kiln) means less mechanical wear on the reactor itself. You trade mechanical maintenance for electrical maintenance. For most modern plant teams, that is a trade worth making.

Application: Waste Tire Recycling

The tire industry is perhaps the biggest adopter of microwave pyrolysis right now. The steel wires inside tires can cause havoc in mechanical shredders, but in a microwave field, the rubber heats up so fast that it separates cleanly from the steel and fiber.

The resulting oil is cleaner, with lower sulfur content compared to conventional pyrolysis oil. This makes it easier to sell back to refineries or use as fuel for generators.

Application: Biomass and Sludge

Sewage sludge and agricultural waste are difficult to handle because they are sticky and wet. Traditional dryers clog.

Microwave systems, often using a belt design like those found in Nasan equipment, handle this well because the heat pushes moisture out as steam from the inside, preventing the formation of a sticky outer shell. The volume reduction is massive, significantly lowering disposal costs.

Technical Considerations: Frequency and Power

Industrial systems typically operate at 915 MHz or 2450 MHz.

2450 MHz: Good for thin layers and smaller throughputs. High heating density.915 MHz: Better penetration depth. Essential for thick beds of material and high-volume industrial applications.

Choosing the right frequency is an engineering calculation based on your material's dielectric constant. Do not guess here; get samples tested.

Safety Protocols in Microwave Processing

We are dealing with high-energy radiation and flammable gases (syngas) produced during pyrolysis. The engineering standards here are rigorous.

Choke mechanisms on the inlet and outlet prevent microwave leakage. Nitrogen purging systems ensure the reactor remains oxygen-free to prevent explosions.

I always advise clients to look for vendors who prioritize safety interlocks. If the belt stops, the microwaves must cut instantly. If the temperature spikes, the nitrogen flood must trigger automatically.

Comparing Footprint and Installation

Real estate in a factory is expensive. A traditional pyrolysis plant requires a massive footprint—burners, fuel tanks, large diameter stacks, and cooling zones.

A microwave pyrolysis unit is surprisingly compact. It is often a linear setup. I have seen facilities retrofit these units into existing warehouse spaces that could never have accommodated a rotary kiln. This allows for decentralized processing—treating waste where it is generated rather than trucking it to a central facility.

Future Trends in Thermal Processing

The industry is moving toward "smart" drying. Sensors inside the cavity monitor the exact temperature of the material in real-time.

Feedback loops adjust the power of the magnetrons instantly. If the feed rate drops, the power drops. This prevents overheating and saves electricity.

We are also seeing hybrid systems that use waste heat from the microwave cooling system to pre-dry the feedstock. It is circular engineering at its finest.

Selecting the Right Vendor

When you are ready to buy, do not just buy a machine; buy support. You need a partner who understands the dielectric properties of your specific material.

Look for manufacturers who offer pilot testing. You should be able to send a ton of your material to their facility and see the results before you sign a check. Nasan has built a reputation for this kind of client engagement, ensuring the machine specs match the reality of the production floor.

ROI Calculation: A Practical Example

Consider a plant processing 20 tons of sludge per day.

Disposal cost: $100/ton.Traditional Drying Cost: $40/ton (mostly gas).Microwave Drying Cost: $25/ton (electricity).

The savings on processing alone are significant ($300/day). But the real kicker is volume reduction. If you reduce the mass by 80%, you are now only paying disposal on 4 tons. Your daily disposal bill drops from $2000 to $400.

That is a daily saving of over $1,900. The ROI timeline becomes very attractive.

The shift from fossil-fuel-based heating to electromagnetic heating is not a fad; it is the inevitable direction of industrial processing. Microwave pyrolysis offers a level of control, speed, and efficiency that old thermal methods simply cannot match.

While the technology requires a shift in mindset—moving from mechanical dominance to electrical precision—the payoffs in yield quality and operational costs are undeniable. Whether you are recovering carbon black or reducing hazardous sludge, the math falls in favor of microwaves.

If you are serious about modernizing your line, reach out to established manufacturers like Nasan. Get your material tested, run the numbers, and build a facility that is ready for the next twenty years of industry standards.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: How does microwave pyrolysis differ significantly from incineration?

A1: Incineration involves burning material in the presence of oxygen, which produces ash and CO2. Microwave pyrolysis occurs in an oxygen-free environment. Instead of burning, the material decomposes chemically into valuable byproducts like bio-oil, syngas, and char, which can be captured and sold rather than released into the atmosphere.

Q2: Can this technology handle materials with very high moisture content?

A2: Yes, actually better than many traditional methods. Since water absorbs microwave energy very efficiently, the technology is excellent for wet feedstock like sludge or biomass. The internal heating rapidly vaporizes water without the formation of a thermal insulating crust, resulting in faster drying and decomposition times.

Q3: Is the electricity consumption prohibitively expensive?

A3: While the unit cost of electricity is often higher than natural gas, the efficiency of microwave pyrolysis offsets this. Energy transfer is nearly 100% efficient (entering the material directly), whereas gas burners lose massive amounts of heat to the exhaust and the equipment structure. For many processes, the total energy cost per ton of finished product is lower.

Q4: What types of materials are best suited for this process?

A4: Materials with good dielectric properties (the ability to absorb microwave energy) work best. This includes waste tires, carbon-based biomass, sewage sludge, plastics, and medical waste. If a material is transparent to microwaves, it can still be processed by mixing it with a "susceptor" material (like carbon) that absorbs the energy and heats the batch.

Q5: What is the typical maintenance schedule for a microwave pyrolysis unit?

A5: Maintenance primarily focuses on the electrical components rather than heavy mechanics. The magnetrons (microwave generators) are the main consumable and typically last between 5,000 to 8,000 hours depending on usage. Conveyor belts and cooling systems require standard routine checks, but there is significantly less wear and tear compared to the rotating steel drums of traditional kilns.