The harvest is finished, but the work is far from over. For farmers and agricultural processors, the period immediately following harvest is the most critical. Freshly harvested crops often contain high levels of moisture, which is the primary enemy of long-term storage. Without immediate intervention, mold growth, insect infestation, and spoilage are inevitable. This is where a reliable grain dryer becomes the cornerstone of a profitable agricultural operation.

In the past, many operations relied on sun drying. While cheap, this method is inconsistent and weather-dependent. It exposes the crop to birds, rodents, and environmental contaminants. As production scales up, relying on the sun is no longer feasible.

Modern industrial agriculture demands precision. A mechanical drying system provides control over the process, ensuring that tons of product can be stabilized within hours rather than days. Manufacturers like Nasan have recognized this need, developing systems that prioritize consistent airflow and energy efficiency to handle large volumes without compromising grain quality.

The Science of Moisture Reduction

Understanding the physics behind drying is essential for operating machinery effectively. A grain dryer does not simply heat the product; it manages the moisture migration from the inner kernel to the outer husk.

Every grain has an Equilibrium Moisture Content (EMC). This is the point where the grain stops gaining or losing moisture based on the surrounding air. The goal of the machine is to manipulate the air’s temperature and humidity to lower that equilibrium point.

If you heat the air, its relative humidity drops, making it "thirsty." It pulls water from the grain. However, if you extract moisture too fast, the outer layer of the kernel dries and shrinks while the inside remains wet. This causes stress cracks, which lowers the market grade of the product.

H2: Types of Grain Dryer Systems in the Industry

There is no "one size fits all" solution in grain processing. The choice of equipment depends heavily on the volume of the harvest and the specific type of crop being handled.

Batch Drying Systems

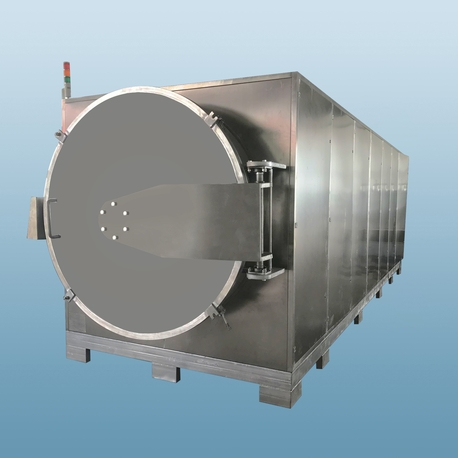

For smaller to medium-sized operations, batch dryers are common. A specific amount of grain is loaded into the chamber, dried to the target moisture level, cooled, and then unloaded. This allows for strict control over distinct lots, which is useful if you are processing different varieties of crops in a single season.

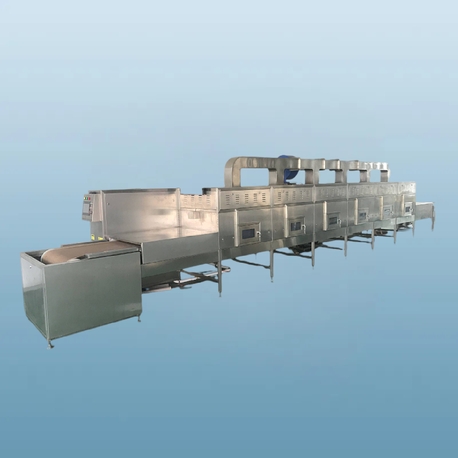

Continuous Flow Dryers

Large commercial silos and depots typically use continuous flow systems. Wet grain is constantly fed into the top, and dry grain is discharged from the bottom. These systems are designed to run 24/7 during the peak harvest window. They require sophisticated sensors to monitor the moisture of the incoming and outgoing product to adjust the dwell time automatically.

Mixed-Flow vs. Cross-Flow

In a cross-flow design, air moves perpendicular to the grain column. This is simple but can result in uneven drying. Mixed-flow dryers offer better uniformity. They mix the grain as it descends, ensuring every kernel receives equal exposure to the hot air. This uniformity is critical for maintaining the milling quality of crops like rice and wheat.

The Operational Workflow

Implementing a grain dryer into your facility requires a structured workflow. The efficiency of the machine is often dictated by how well the surrounding logistics are managed.

1. Pre-Cleaning

Before grain enters the dryer, it must be cleaned. Chaff, straw, and dust block airflow. If these "fines" accumulate in the drying chamber, they create hot spots. These hot spots are a primary cause of dryer fires and reduce the overall efficiency of the fan system.

2. Loading and Tempering

Grain should be loaded evenly. In some advanced processes, "tempering" is used. This involves heating the grain and then letting it sit without airflow for a short period. This allows moisture from the center of the kernel to migrate to the surface, making the subsequent drying phase more efficient.

3. The Drying Phase

The operator sets the plenum temperature. Corn can withstand high temperatures (often up to 110°C for animal feed), while milling wheat or paddy rice requires much lower temperatures (below 60°C) to prevent damaging the starch or cracking the hull.

4. The Cooling Phase

This is a step that is often rushed but shouldn't be. You cannot put hot grain into a storage silo. It will cause condensation on the silo walls, leading to spoilage. The grain must be cooled to within a few degrees of the ambient temperature before storage.

Energy Efficiency and Cost Management

Fuel costs are the single largest operating expense in grain drying. Whether using natural gas, propane, or biomass, the cost to remove a point of moisture affects the final profit margin.

Modern engineering focuses heavily on heat recovery. Many systems now capture the warm air from the cooling section (which has picked up heat from the hot grain) and recycle it back into the heating burner. This reduces the amount of cold air that needs to be heated from scratch.

Innovations by brands such as Nasan often integrate advanced insulation and airflow management. By preventing heat loss through the dryer walls and ensuring optimal air-to-grain contact, these systems reduce the BTUs or kilowatts required per bushel. In a high-volume season, a 10% increase in thermal efficiency can save thousands of dollars.

Handling Sensitive Crops

Not all crops react to heat in the same way. A versatile grain dryer must be adjustable to handle the specific biological characteristics of different harvests.

Paddy Rice:Rice is perhaps the most difficult grain to dry. If dried too quickly, the kernel fissures. When milled later, these fissured kernels break. Broken rice commands a much lower price than whole head rice. Therefore, rice drying involves lower temperatures and longer dwell times.

Soybeans:Soybeans are fragile. Their skins can split easily if the humidity is too low. Often, operators will use natural air drying or very low heat to preserve the integrity of the bean, especially if it is intended for seed.

Corn (Maize):Corn generally has a high moisture content at harvest (sometimes 25% or more). It requires robust drying power. Because the kernel is tough, high airflow and high heat are standard to handle the sheer volume of water removal required.

Solutions for Safety and Maintenance

Industrial drying involves heat, fuel, and combustible dust. This combination presents safety risks that must be managed through design and protocol.

Fire Prevention

Dust accumulation inside the plenum is dangerous. Regular shutdowns to clean the internal screens are necessary. Modern dryers are equipped with fire detection sensors that monitor the exhaust air temperature. A sudden spike triggers an automatic shutdown of the burner and fans.

Moisture Sensor Calibration

You cannot manage what you cannot measure. The moisture sensors at the discharge point dictate the speed of the dryer. If these are inaccurate, you might over-dry the grain (wasting fuel and losing sellable weight) or under-dry it (risking spoilage). These sensors should be calibrated against a benchtop tester daily.

Fan Maintenance

The fans are the heart of the system. If a fan belt slips or a blade becomes unbalanced, airflow drops. Reduced airflow means the burner might overheat the air that is moving, scorching the grain. Regular mechanical inspections ensure the airflow remains at design specifications.

The Economic Impact of Proper Drying

Investing in an industrial grain dryer is not just about preventing rot; it is a strategic marketing tool.

When farmers are forced to sell wet grain immediately at harvest, they sell into a saturated market. Prices are typically at their lowest. Furthermore, elevators charge "shrinkage" fees and drying fees to accept wet grain.

By drying on-site, the producer controls the inventory. Dry grain can be stored for months. This allows the producer to wait for the market price to rebound later in the year. The ability to sell a finished, stable product directly to end-users (like feed mills or food processors) captures more value.

Additionally, consistent moisture content improves the processing characteristics. Millers and crushers prefer to buy from suppliers who can guarantee a specific moisture level, as it makes their own machinery run more smoothly.

Automation and Future Trends

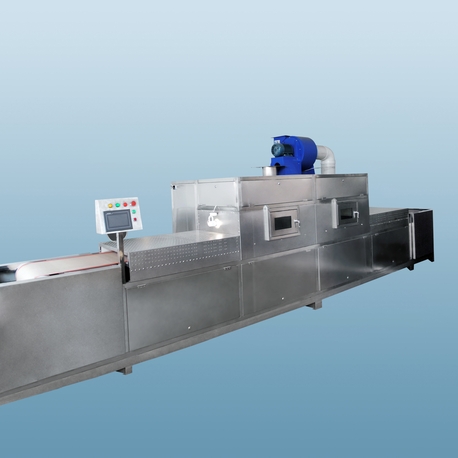

The days of manually adjusting gas valves are fading. The future of the grain dryer lies in full automation.

Smart control panels now link to mobile apps, allowing farm managers to monitor plenum temperatures and discharge moisture levels from their phones. Algorithms can predict the drying rate based on incoming grain conditions and weather forecasts, adjusting the burner intensity in real-time.

We are also seeing a shift towards alternative fuels. While propane remains king, biomass burners (using corn cobs or rice husks) are gaining traction in regions where fossil fuel is expensive. Heat pump technology, an area where companies like Nasan have expertise, is also being adapted for grain applications to lower the carbon footprint of the drying process.

The transition from field to storage is the defining moment for crop quality. No matter how good the growing season was, a poor drying process can ruin the value of the yield. A high-quality grain dryer provides the consistency, speed, and safety required to secure that value.

From managing delicate paddy rice to processing high-moisture corn, the technology has evolved to meet the rigorous demands of modern agriculture. By focusing on thermal efficiency, precise moisture control, and robust safety features, producers can turn their harvest into a stable, global commodity. Whether upgrading an existing facility or building a new one, choosing partners with engineering depth, such as Nasan, ensures that the infrastructure will perform season after season.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the ideal temperature for drying corn versus wheat?

A1: The temperature settings depend on the end-use of the grain. Generally, corn intended for animal feed can be dried at higher temperatures, often between 90°C and 110°C (190°F - 230°F). However, wheat, especially if intended for milling or baking, is more sensitive to heat damage. It is typically dried at lower temperatures, usually between 50°C and 60°C (120°F - 140°F), to preserve the gluten quality.

Q2: How much moisture can a grain dryer remove in one pass?

A2: Most continuous flow dryers are designed to remove between 5% and 10% moisture in a single pass efficiently. If the grain is extremely wet (for example, corn harvested at 30% moisture needing to get to 15%), it is often better to pass it through the dryer twice or use a very slow speed. Trying to remove too much moisture too quickly can cause the kernels to harden on the outside and trap moisture inside.

Q3: Why is cooling the grain necessary after drying?

A3: Cooling is critical to prevent condensation. If you place hot grain into a storage bin, the air inside the bin will heat up. When this warm air hits the cold metal walls of the bin (especially at night), water condenses and drips back onto the grain. This leads to mold growth and crusting. Grain should be cooled to within 5°C to 8°C of the outside air temperature before long-term storage.

Q4: Does a grain dryer require a specific type of fuel?

A4: The most common fuels for commercial dryers are natural gas and liquid propane (LPG) because they burn cleanly and provide high heat. However, there are dryers designed to run on fuel oil, biomass (like wood chips or crop residues), and even electricity. The choice depends on local fuel availability and cost. Heat pump dryers are becoming popular for their energy efficiency, though they typically operate at lower temperatures.

Q5: How do I prevent fires in my grain dryer?

A5: Fire prevention starts with cleanliness. "Fines" (dust and red dog) are highly flammable. You must clean the intake screens and the plenum chamber regularly to prevent buildup. Additionally, never bypass safety sensors. Ensure your high-limit temperature switches are functional, and keep the grain moving. A stopped dryer with the burner on is a major fire hazard.